Working With Repeated Information

Repeated information, groups, and data structures (are all the same thing)

Many variables are 1 to 1. Each person has one birthdate, one full name, etc. But right away we run into information where one person has more than one of the same kind of thing. For example: each person might have more than one phone number; child; and more.

One way to handle that could be to make a bunch of variables: child1, child2, etc. That gets messy fast! In computer programming, we can replace a bunch of variables with one variable that stores that repeated information, giving it a single variable name like children. Those special variables are called data structures in computer science. Docassemble calls them "groups". The most common data structures you will run into in Docassemble are lists, dictionaries, and sets.

Introduction to lists

The first kind of data structure you should learn about is called a list. Lists can store any kind of repeated information: numbers, text, objects, or even other lists. Lists are similar to arrays in other computer programming languages.

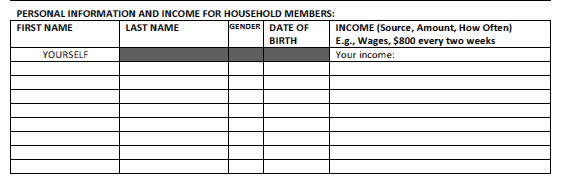

Here's a portion of a real paper intake form from Greater Boston Legal Services:

Right away, the first thing you might notice is that our form can only handle up to 9 people. That probably is plenty for most households, but not every household (I come from a family of 11!).

If we wanted to model this intake form in Docassemble, we might start out by using a list named household_members.

Below is a short Python program that demonstrates two ways to handle a list of children: as separate variables, and as one list.

Click the "run" button to run the code sample. After you have run it once, change the value of use_variables to False and run it again.

For easy reference, here is the full code:

use_variables = True

child1 = "James"

child2 = "Alice"

child3 = "Richard"

children = ["Alexandra","Robert","Lisa"]

if use_variables:

print(child1)

print(child2)

print(child3)

elif not use_variables:

for child in children:

print(child)

We can see that using several variables and using a list can get us to the same outcome. But using the list is more flexible: we can keep track of many items without having to create a variable name for each item in advance.

Accessing items in a list

Once we have created a list, we can access the items in it like this:

children = ["Jenny","Shakira"]

children[0]

Try copying and running the code above (one line at a time) in the interactive Python console below:

The number in the square brackets is called an index. In Python, the first item in a list has an index of 0, not 1.

Inside the computer, our list is stored like a spreadsheet:

| Index | Value |

|---|---|

| 0 | Jenny |

| 1 | Shakira |

| 2 | Beyonce |

We read down to the row (index) we want to find the value stored in that row.

After running the code above, try typing children[1]. What value does it have? What happens if we try to access children[2]?

Changing the value of a list

Changing the value of an item in a list is the same as changing the value of a variable. We use the item's index to say which item we want to change:

children[1] = "Sean"

You can add items to a list by using .append(), like this:

Try adding a new name to the list.

Here's the code for reference:

children = ["Alexandra","Robert","Lisa"]

print(children)

children.append("Miles")

print(children)

Deleting an item in a list

You can delete an item in a list two different ways: by value, or by index.

By value, using .remove():

shopping_list = ["Eggs","Milk","Cereal"]

shopping_list.remove("Milk")

print(shopping_list)

By index, using .pop():

shopping_list = ["Eggs","Milk","Cereal"]

shopping_list.pop(1)

print(shopping_list)

for loops

In the first example, we used a for loop to print the name of each child. Let's take a closer look at that now.

children = ["Alexandra","Robert","Lisa"]

for child in children:

print(child)

When you use a for loop like the one above, Python will run the same series of actions for each item in the list. The variable child is a temporary variable. Each time the loop runs, the value changes.

- On the first loop,

childis equal to "Alexandra" - On the second loop,

childis equal to "Robert" - On the third loop,

childis equal to "Lisa"

The DAList class in Docassemble

When you use a list in Docassemble and want it to handle collecting items for you, you will create an object of class DAList instead of creating it using my_list = []. Once you've done that, you can access/modify, and otherwise work with the items the same way you do in Python.

As a reminder, we use the objects block to create a Docassemble object. Here's an interview that creates a DAList:

objects:

- my_list: DAList

You can read Docassemble's documentation about lists.

More explorations of lists

- https://www.w3schools.com/python/python_lists.asp

- https://teachcomputerscience.com/gcse-python/lists/

Dictionaries

Like a list, a dictionary is a data structure that can store repeated information. The main difference is that in a list, the index is numeric. In a dictionary, the index is a keyword. Dictionaries are similar to associative arrays or hashtables in other computer programming languages.

If a list is a good way to store a unknown number of items, a dictionary is a good way to store an unknown number of items that match exactly one category.

Sticking with our intake analogy, let's think about an intake that asks someone to report all of their expenses. We know everyone has some expenses, and we want to be able to work with each expense separately. For example:

- Rent

- Food

- Utilities

- Credit card payments

- Student loan payments

- Medical bills

Here's a small example of a Python dictionary:

Run the code sample above. Notice that when we use a for loop on this dictionary, on each loop the variable gets the keyword, or index of the dictionary.

A python dictionary is created with curly braces, like this: {}. Each entry is a keyword, followed by a : and then a value. Commas separate multiple pairs of key/value.

Accessing items in a dictionary

Once we have created a dictionary, we can access items in it like this:

expenses = {

"rent": 1000,

"utilities": 300,

"food": 400,

"credit cards": 120,

"student loans": 1000,

"medical bills": 200

}

print(expenses['rent'])

This is very similar to how we access an item in a list. A dictionary is a lot like a spreadsheet where each row has a unique name instead of a number. The difference is that the index can be a descriptive word (or even a sentence) instead of a number. A dictionary item's index is called a key.

| Key | Value |

|---|---|

| rent | 1000 |

| utilities | 300 |

| food | 400 |

For a quick example of why using a dictionary is powerful, let's introduce the sum() function. Try running the code sample below.

Try changing some of the numbers and see how the value that is printed out changes at the same time.

In the example above, we use the .values() method of a dictionary to get all of the values as one list. Then we used sum() to add all of the numbers together. Storing items in a dictionary lets us label them, while still working on them as a group. It gives us a little more context than a list, where we only would know that one expense was the first, second, third, and so on.

Adding a new item to a dictionary

You can add a new item to a dictionary simply by referencing a key that you haven't used yet. Referencing an existing key will change the value stored at that key.

Run the code sample below. Try adding an expense for automobile insurance.

Docassemble's DADict class

When you use a dictionary in Docassemble and want it to handle collecting items for you, you will create an object of class DADict instead of creating it using my_dict = {}. Once you've done that, you can access/modify, and otherwise work with the items the same way you do in Python: you can refer to my_dadict["keyword"] and use the method .update() to combine two DA dictionaries.

As a reminder, we use the objects block to create a Docassemble object. Here's an interview that creates a DAList:

objects:

- my_dict: DADict

You can read Docassemble's documentation about dictionaries.

More explorations of dictionaries

Introduction to sets

Sets come from the world of mathematics: think Venn diagrams. In a set, each item can only appear exactly once. No duplicates allowed. Items in a set don't have an index or a key, unlike items stored in dictionaries and lists.

Suppose you go on a bird watch. You want to know how many different species of birds you see. If you store the names of each bird in a set, each bird species appears only once, so you don't have to worry about duplicates.

Run the code sample below.

Notice that when we stored the bird names in a list, we had duplicates. When we use a set instead, each bird species only appears one time. Try adding a new bird species to both the set and to the list and see what happens when you run it again.

An alternative Python way to create a set is with curly braces, like the example below:

birds = {"Blue jay","Pileated woodpecker","Ivory billed woodpecker"}

Accessing items in a set

An item is in a set, or not. It doesn't have an index or a key. The items don't have any order to them. You can use standard mathematical operations on a set, such as Union, Intersection, Difference, etc. You can use a for loop to work on the whole list at once.

birds = {"Blue jay","Pileated woodpecker","Ivory billed woodpecker"}

for bird in birds:

print(bird)

See the explorations below for more about operations on sets, including use of the union and intersection operators.

Turning lists into sets

Sometimes, you may want to collect everything in a list, and then turn it into a set later, so you can keep track just of the unique values.

You can do that with set(). Try running the code sample below:

Docassemble's DASet class

When you use a dictionary in Docassemble and want it to handle collecting items for you, you will create an object of class DASet. Once you've done that, you can work with the items the same way you do in Python. Use the method .update() to combine two DASets.

As a reminder, we use the objects block to create a Docassemble object. Here's an interview that creates a DASet:

objects:

- my_set: DASet

You can read Docassemble's documentation about sets.

More explorations of sets

Groups and objects work well together

Groups can store all kinds of information. One of the most common things to store in a group is an object.

If we go back to our spreadsheet metaphor, lists and dictionaries are just two columns in a spreadsheet. If we store an object in a list, now we suddenly have a whole table.

Thinking back to our intake sheet, for each household member we collected:

- First name

- Last name

- Gender

- Birthdate

- Income

On paper, we could represent that as a table:

| First name | Last name | Gender | Birthdate | Income |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jane | Smith | F | 10/1/2000 | SSI |

| Robert | Smith | M | 1/25/1997 | Employment |

Or in a Python list of Individual objects, with each column representing an attribute of our object:

| Index | name.first | name.last | gender | birthdate | income_type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Jane | Smith | F | 10/1/2000 | SSI |

| 1 | Robert | Smith | M | 1/25/1997 | Employment |

Docassemble lets you work with lists, dictionaries, and sets of objects. They just work better together. On one screen, you can collect all 5 fields for each household member, and store them as one object in the list, dictionary, or set.

You don't need to create your own objects to store them in lists. Docassemble lets you store the built-in DAObject in a list, which can have attributes added in your interview without requiring you to do any special setup.

Using Docassemble Groups to Collect Information

Special variable i

You can always treat a group like an ordinary variable, and simply use the square bracket syntax, like this: - User name: names[1]. However, that has no advantage over using ordinary variables, like name_1, name_2, etc.

Instead, Docassemble offers a convenient placeholder: the special variable i. In a Docassemble interview, the variable i always refers to an item inside a list. A question that refers to children[i] will work for any item in the list children.

Here's an example:

---

question: |

Tell us about this child

fields:

- First name: children[i].name.first

- Last name: children[i].name.last

- Birthdate: children[i].birthdate

datatype: date

The one question we wrote above will work for the first, second, third, etc. child, without us having to write a different question for each child.

You might want to let someone know what child number they are answering a question about. You can use the variable i to help with that, too. The built-in function ordinal() will take a list number, and return "first" for the first item (which has index 0, remember, because lists start at zero), "second" for the second item, and so on. Here's a short interview that uses this function:

---

question: |

Tell us about your ${ordinal(i)} child

fields:

- First name: children[i].name.first

- Last name: children[i].name.last

This would display on the screen as Tell us about your first child.

Note: if you are working with a list of lists, or even a list of lists of lists, you can use the variables

i,j,k,l,m, andnall on the same screen. E.g.,list1[i].children[j].income_sources[k]. Because of Docassemble's object structure, you rarely need to do this. It's more common to use thegeneric objectfeature for those lower levels.

The .using() method of an object

One DAList object can work 4 different ways. To configure those options, Docassemble expects us to set an attribute on the object. One way to do that is to use the method .using(). Briefly, .using() lets you set the attribute of an object at the same time that you create it. We do that with keyword parameters.

Here's a regular object block:

---

objects:

- my_object: DAObject

Let's say we want to set the favorite_color attribute of our object to "Blue". One way is with the .using() method:

---

objects:

- my_object: DAObject.using(favorite_color="Blue")

Another way would be to set it in a mandatory code block:

---

objects:

- my_object: DAObject

---

mandatory: True

code: |

my_object.favorite_color = "Blue"

Or of course, in a question:

---

objects:

- my_object: DAObject

---

question: |

What is the object's favorite color?

fields:

- no label: my_object.favorite_color

The .gather() method and other ways to trigger gathering

There are two ways to trigger gathering a group in Docassemble:

- Using the .gather() method of the list in a mandatory code block, or

- Referencing the full list: in a code block, a question's text, or a template.

Here's an example code block:

---

mandatory: True

code: |

children.gather()

And here's a question:

---

question: |

List of children

subquestion: |

${children}

If you want to control when the items of a list will be collected, using the .gather() method is a neat and explicit way to do so. But referencing the list is just fine.

Methods of collection

There are four recommended ways to use groups in Docassemble. These apply to lists, dictionaries, and sets:

- Ask for the number of items in the group up front. Docassemble will handle showing a separate screen to collect each item.

- After collecting each item, ask if the user has more items to add. Docassemble will keep going until your user answers "no".

- Gather the whole group on one screen, letting the user click a button to add a new item.

- Pre-fill the group with prompts or using computer code, and allow your user to edit and add more later.

Which method you use depends on your intuititions (and testing) about the best user experience.

Some kinds of information we naturally number, and some we don't. For example: if we are prompted to list our children, we know how many children we have. If we are prompted to list our assets, we might never have counted them up individually. Asking how many bank accounts we have gives us extra work instead of making it simpler. Think about the information you're gathering and which method works best.

Similarly, some information is a good fit for gathering on a single screen, and some is too complex. In our household example, 5 fields might be too many to try to fit multiple rows on a small screen. Usually the on-one-screen method works best when you're collecting 3 or fewer fields for each item.

Asking for the number up front

One way to use a Docassemble list is to ask the user for how many items they are going to gather up front. Let's walk through this process with gathering a list of children.

Asking for the number up front requires us to use two special attributes of a DAList: .ask_number and target_number. We are collecting a list of objects, so we also need to tell Docassemble what kind of object our list will hold with the object_type attribute.

First, let's create our DAList object:

---

objects:

- children: DAList

We want to use the list style that asks the user how many of that item they have. We do this by setting the ask_number attribute to True. Let's do that with the .using() method. Modify the objects block so it looks like this:

---

objects:

- children: DAList.using(ask_number=True)

We'll use the class Individual to represent each child in our list. To tell Docassemble what class of object we are storing in the list, modify it one more time:

---

objects:

- children: DAList.using(ask_number=True, object_type=Individual)

By setting the object_type, Docassemble will handle creating new objects for us as needed, any time we add a new item to the list.

Next, we want to set the target_number attribute of our DAList so we know how many children our user has. Let's do that with a question. Add the block below to your interview:

question: |

How many children do you have?

fields:

- no label: children.target_number

datatype: integer

Datatype integer represents a whole, round number (instead of a number with a decimal point). We need a whole number for target_number. We can't collect 1/2 of a kid!

Now, we just need a question to get information about each child:

---

question: |

Information about your ${ordinal(i)} child

fields:

- First name: children[i].name.first

- Last name: children[i].name.last

Asking after each item is gathered

The default way to gather items in a list is to ask, in order:

- are there any items in the list? with the attribute

.there_are_any - Tell us about the first item (with whatever attributes of the item are required)

- Are there any more items? with the attribute

.there_is_another

Because this is the default, if you use this method, you don't need to set any options with .using(), other than the object_type.

Each of these questions appear on a different screen. In some cases, this can be quite tedious, but sometimes it offers the best user experience.

Let's show a short example:

---

mandatory: True

code: |

children.gather()

ending_screen

---

objects:

- children: DAList.using(object_type=Individual)

---

question: |

Do you have any children?

yesno: children.there_are_any

---

question: |

What is your ${ordinal(i)} child's name?

fields:

- First name: children[i].name.first

- Last name: children[i].name.last

---

question: |

Do you have any more children?

yesno: children.there_is_another

---

event: ending_screen

question: |

Here are your children

subquestion: |

${children}

Asking for multiple items on one screen

If you only need a few pieces of information for each item in your list, collecting them all on one screen can be a good user experience.

We still need to ask one preliminary question: are there any items on the list? with the attribute .there_are_any. But we no longer have to answer if there are any more items. The way to trigger this is to add the specifier list collect: True to the bottom of the question that asks the users for the details of each list item.

This method only works for a list, and not for a dictionary or set.

Here is a short interview that uses this technique:

---

mandatory: True

code: |

children.gather()

ending_screen

---

objects:

- children: DAList.using(object_type=Individual)

---

question: |

Do you have any children?

yesno: children.there_are_any

---

question: |

What is your ${ordinal(i)} child's name?

fields:

- First name: children[i].name.first

- Last name: children[i].name.last

list collect: True

---

event: ending_screen

question: |

Here are your children

subquestion: |

${children}

In some cases, you might know that there is at least one option. For example, collecting members of a corporate board. Then, you could set .there_are_any to True with a .using() statement, like this:

---

objects:

- board_members: DAList.using(object_type=Individual, there_are_any=True)

By default, the list collect screen has buttons to delete each item, as well as a number next to each item. Read more about how to customize the appearance.

Using code to pre-fill items, with or without prompts

Sometimes, we want to use code to gather items in a list, or otherwise gather the items without Docassemble triggering the questions manually. To do so, we need to set the auto_gather attribute to False. Then, once we have finished gathering the items into our list, we need to set the .gathered attribute to True.

Here is a short example:

---

mandatory: True

code: |

# For simplicity, "Bob" and "Jane" are just text, and not Individual objects as in the other examples

children.append("Bob")

children.append("Jane")

children.gathered = True

ending_screen

---

objects:

- children: DAList.using(auto_gather=False)

---

event: ending_screen

question: |

Here are your children

subquestion: |

${children}

Display information from a Docassemble Group on screen or in a template

Using the built-in comma_and_list() method

One easy way to display a list is to simply reference the list's name. The list's __str__() method displays each item, in order, separated by a comma and with the word and before the final item. It does this with a built-in function named comma_and_list().

For example, if you have a DAList people with items ["bob","jane","roger"] and you reference it as ${people}, the output will be bob, jane, and roger.

Using a for or while loop

If you want more control over displaying the items in your list--for example, you want to display just the first names, and not the last names--you will need to use a loop.

You can read more about the for and while loop in the section about Python.

A for loop in Python:

- Takes some action

- For each item in the list, set, or dictionary

The basic structure is the keyword for, followed by a temporary variable name, the keyword in, and finally followed by the name of the list, dictionary, or set.

In a Python code block, you will write a for loop just like an if statement, with the start/end shown by indentation.

for item in my_list:

do_something(item)

Just like an if statement, when you use a for loop inside a question block, you need to start the line with a % symbol, and you need to explicitly end it, with the endfor keyword. For more, you could review the section on Mako. Here's what it looks like in a short example:

---

mandatory: True

code: |

items = ['A','B','C']

ending_screen

---

event: ending_screen

question: |

% for item in items:

* ${item}

% endfor

Remember, the for loop takes each item in the list, dictionary, or set, and assigns that item to a temporary variable. That makes it possible to work with each item one at a time.