Object Oriented Programming in Docassemble

Overview of Classes

Objects are a special type of variable. Instead of holding one piece of information, they can hold several at once. For example, the variable x can easily represent the number 10. But what if you wanted a variable to refer to, for example, an apple? You might want to store several pieces of information about the apple at once. Perhaps you want to know its weight, color, and variety.

You could store the information in several variables, like this:

apple_weightapple_colorapple_variety

Suppose you need to keep track of 10 different apples. Now you have:

apple2_weightapple2_colorapple2_variety... and so on

This can quickly become hard to manage. What's more, each time you make a new variable to represent an apple, you introduce the risk of making a mistake.

In object-oriented programming, you can more easily keep track of your variables by writing a kind of blueprint, or class definition that lets you group the related variables together. Once it's part of an object like, this, we call the individual variables attributes. An object is an instance of a Class with one or more of those attributes filled-in with specific values.

You can think of a classes' definition as the column labels in a spreadsheet:

| object | weight | color | variety | calories |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| apple1 | 300 grams | red | Red delicious | 75 |

| apple2 | 270 grams | green | Granny Smith | 72 |

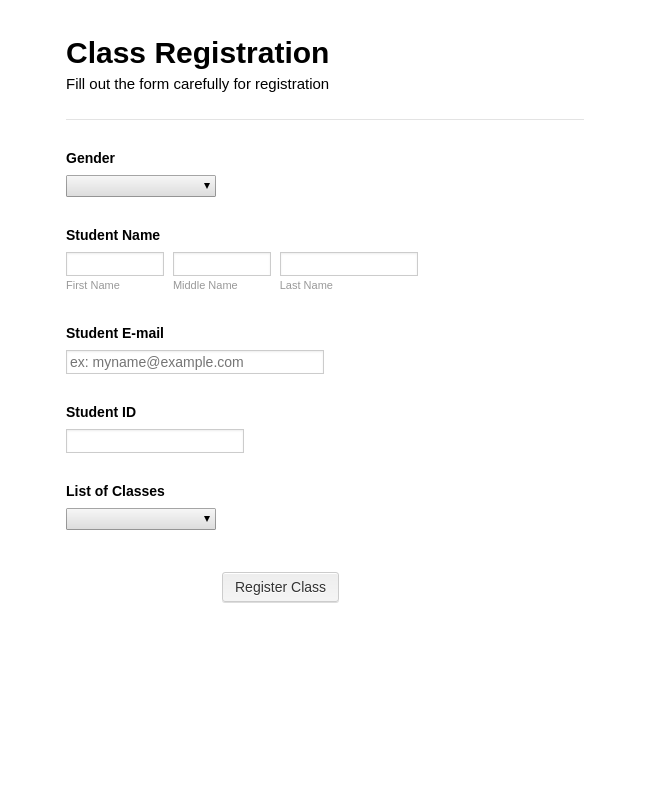

Or perhaps a blank form:

In both cases, what the class definition does it give the individual variables a structure. It provides a meaning to a collection of variables, so that every time you create an object, each object will have the same basic outline and you can use it the same way.

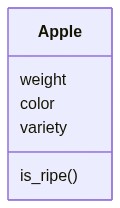

One way to keep track of the different attributes and methods of a class is with a special kind of diagram, called a UML class diagram.

Here is a UML diagram that represents the Apple class:

The basic structure of a UML diagram is three boxes:

- the class name at the top

- An optional list of attributes in the middle

- An optional list of methods at the end

UML diagrams are just one way to represent a class. It's a standard that can make it easy to quickly communicate the list of different kinds of information that the class contains.

We also often list the type of each variable after its name in this diagram. In the example diagram, weight is a floating point number, or float (has a decimal). Color and variety are text, or str types.

Sometimes a class's attributes themselves are classes. You'll see this is common in Docassemble's built-in objects.

Class methods

So far our metaphor has concentrated on information, but something special about objects is that you can also group methods with the object definition. A method is a function that is part of a class definition. When you run an object's method, you are taking an action that uses the information in the class and gives you back something new, such as a true/false value, a number, or text that you can display on the screen.

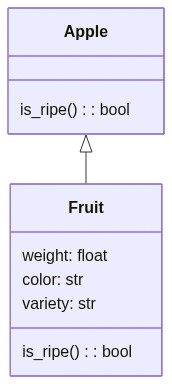

For example, an apple might have a method is_ripe() that uses the planted_date and today's date to tell you if the apple is ready to be picked. It would return True if the apple is ripe, and False if it isn't ready.

Here's the updated diagram that shows the is_ripe() method:

If we had an Apple object named jons_apple, we could display its ripeness in our interview like this: ${jons_apple.is_ripe()}.

Inheritance

A useful aspect of classes is that one class can rely on, or inherit, the definition of a different class. We call the more generic class the parent and the more specific class the child or sub-class. Below, the Apple class inherits from the more generic fruit class. It has its own is_ripe() method, because different kinds of fruit ripen at different times. But it can use all of the same attributes as the original Fruit class.

One benefit of inheritance is reducing the code you need to write. But inheritance also allows you to write your own very specific class, such as Macoun or Cortland, without having to update any functions in your program that might expect to work on every kind of Apple or even Fruit.

Any function that expects to work with a Fruit object will also be able to work with an Apple object if the Apple object inherits from the Fruit class. Inheritance lets you layer on new features without breaking compatibility with the old one.

Object conventions and syntax

Naming conventions

One convention that is true for almost every programming language that has objects is that we use capital letters at the beginning of words, and without spaces, for class names. For example, if we have a class the represents rectangles, we would normally name it Rectangle or maybe FourSidedFigure. This capitalization style is called Pascal Case after the first programming language to use this variable naming standard, Pascal. (Another name for this style is sometimes camel case, although "camel case" is often reserved for variable names where only the second word is capitalized, looking a little like a camel's hump.)

When you see a name written in PascalCase style, it's a good clue that you are looking at a class name.

When you use an object, you still use lower case names with underscores between each word for variable names. For example, my_apple could be an instance of the Apple class.

Using variables and methods

You access an object's attributes by using . dot notation. This simply means the name of the attribute comes after the object's name, separated by a .. For example: my_apple.weight = 100.7.

Methods also use dot notation. Like functions, you call a method with two parentheses after the method's name: apple.is_ripe(), optionally with one or more parameters. apple.nutritional_value("human").

Special class constructor methods __init__() and init()

Python Classes all have a special method, named __init__. This is called the class constructor.

Note: if you write your own class, Docassemble objects should never directly replace the

__init__()method. Instead, you will use the methodinit().

Any time that Docassemble (or Python) creates a new object of this class, the __init__ method will run.

What is the purpose of a class constructor? The class constructor does any setup work that your object needs. For example: it could take the parameters and assign them to attributes to use later; it could run some calculations in advance; or download information from the Internet that it stores for faster access. Just like regular functions and methods, sometimes a class constructor has parameters. For example, a class that represents a Rectangle might have two parameters: side1_length, and side2_length.

Special method __str__()

Objects have another special built-in method that they expect to see, named __str__(). The __str__() method will return a string (text) representation of the object. This is very useful for use inside Docassemble, as we often display information on the screen. For example, the standard string representation of a person is: person.name.first + person.name.middle + person.name. Using the __str__() method allows you to just mention the person object without having to write out first name, last name, etc.

${user}

Is the equivalent of writing:

${user.__str__()}

Think of __str__() as a convenient shortcut. It runs anytime you write the object's name that Docassemble expects to see text, like in an interview or in a template.

Writing ${user} would print out Quinten Steenhuis if user.name.first is Quinten and user.name.last is Steenhuis.

Classes in Docassemble

OK. So far, we learned that an object is a type of variable that can store different, related information in one place. You may not create your own classes for some time. However, this background is helpful for making use of Docassemble's built-in helper classes, methods, and functions that expect to work on a built-in class.

How Docassemble classes differ

In order to work with Docassemble, every object should inherit from the DAObject class.

You may have seen that in most class definitions, you typically list all of the attributes when you create the class. In Docassemble, missing variable definitions are needed to trigger a question being asked. So, instead, you will normally leave those attributes undefined at the class definition time. You can include a comment that lists all of the attributes, and also make use of those attributes inside methods.

Docassemble objects also expect to know their own name, stored as a special attribute instanceName. If you use an existing class, you don't need to worry about this special feature. Docassemble handles this for you when you use the objects block. If you write your own classes, this is something that is important to know.

Using an object inside Docassemble

The modules block

If you write your own Class, you need to tell Docassemble that you plan to use it with a modules block:

---

modules:

- module_from_other_package

- .module_in_this_package

Module files are just Python code. In the background, the modules block tells Docassemble to import a Python file with the classes and functions you need for your interview.

You do not need to use a modules block for any of the built-in classes. They live in a Python file too, but Docassemble automatically includes it for you.

The objects block

Unlike regular Python/Docassemble variables, objects need to be named and defined before they are used.

You create an instance of an object and assign its name with the objects block:

---

objects:

- user: Individual

Underneath the objects keyword, you can write the names of as many object variables that you need for your

interview. Just like the fields statement, this is a list. On the left of the :, write the variable name

that you want Docassemble to use. On the right, write the name of the class that the object is a member of.

In the background, this tells Docassemble to create a new Python object with the name user. It will also run the __init__() method of the class and do whatever setup is needed for your object.

If your class expects any parameters when you make a new object, you can pass those to the __init__() method with a special Docassemble

method named .using():

objects:

- user: Individual.using(parameter1=value1, parameter2=value2)

You don't need to fully understand this for now. Just remember that sometimes you want to customize your object when you create it. The .using() method is a way to do that inside Docassemble. We'll explain this in more detail when we discuss working with repeated information (Groups).

Working with the object as a variable

Treat object attributes just like ordinary variables. For example, you can use an ordinary Docassemble field to assign the value of an attribute:

---

question: |

Your birthday

fields:

- Enter date: user.birthdate

datatype: date

Docassemble's built-in objects

Docassemble has a large number of built-in Classes, as well as optional Classes designed to simplify legal matters. Many of these are utility classes that help write an interview in a more abstract way, but don't represent real-world objects.

You will most likely use these few classes representing things in the physical world again and again:

Person, representing a legal Person that does not need to be an individual (e.g., it could be a corporation)Individual, representing an individual personNameandIndividualName, representing a nameAddress, representing an address in the real-world, together with its different components (street, longitude/latitude, etc).

They are used throughout Docassemble. Several built-in functions also expect these objects as parameters.

The third party Income class is also useful for working with financial information:

It has several advantages over the Docassemble built-in Classes to represent income information.

You may define your own objects as DAObjects and benefit from the neater method of organizing related attributes in one variable, without needing to write your own class definition.

You will also often work with the DAList and DADict objects, which allow you to gather repeated information.

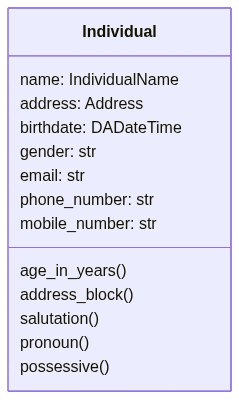

The Individual Class

The Individual class represents a real-world individual. E.g., the person who is using your interview.

Here's a diagram of for the key fields in the Individual class:

Often class diagrams will show the type of each attribute, which the diagram above includes. In the diagram, on the left is the name of the attribute. On the right is the attribute's type. str is the name for text (or string) type variables.

Notice that some of the attributes are also objects, and you need to assign values to attributes of those object, instead of directly at the top level. For example: name and address are objects of class IndividualName and Address. name has attributes first, middle, and last. An address has attributes address (street address), city, state, zip, and unit. See below for more details.

There are some handy shortcuts that you can see in the diagram. age_in_years() does some date math for us. address_block() displays the address in one format (each item on its own line). As well, we can use the hidden __str__() methods when we refer to an Individual (displays the user's full name) or their address (displays the full address on one line).

Here is a sample interview that assigns a value to all of an Individual's built-in attributes:

objects:

- client: Individual

---

mandatory: True

comment: |

We are using this block to control the order of questions

code: |

client.name.first

# We only need to reference one variable on a screen

# to tell Docassemble to show that screen

client.birthdate

client.address.address

show_results

---

question: |

What is your name?

fields:

- First name: client.name.first

- Middle name: client.name.middle

required: False # Not everyone has a middle name, so this is marked optional

- Last name: client.name.last

---

comment: |

In a real question, you should probably make some of these fields optional, such as phone/email.

question: |

Tell us about yourself

fields:

- When were you born?: client.birthdate

datatype: date

- What is your gender?: client.gender

- What is your phone number: client.phone_number

- What is your cell phone number?: client.mobile_number

- What is your email address?: client.email

datatype: email # This uses the email formatting rules to help the user avoid mistakes in typing their address

---

question: |

Where do you live?

fields:

- Street address: client.address.address

- Apartment or Unit: client.address.unit

required: False # Another optional field

- City: client.address.city

- State: client.address.state

- Zip: client.address.zip

---

comment: |

This is an ending screen. It doesn't have any fields, and

we use the event specifier to give it a variable name we can refer to.

event: show_results

question: |

Results

subquestion: |

Hello, ${client}. Your gender is ${client.gender}

Your age is ${client.age_in_years()}

You live at ${client.address}

You can be reached at ${client.email}, ${client.phone_number}, or ${client.mobile_number}.

IndividualName

IndividualName is a pretty simple class. It helps us store the different part of a user's name.

Here is a class diagram for the key fields in the IndividualName class:

When we refer to just an IndividualName, Docassemble runs the .full() method and returns the full name with a middle initial. The .firstlast() method leaves out the middle name. The lastfirst() method shows the name like this: Last, First.

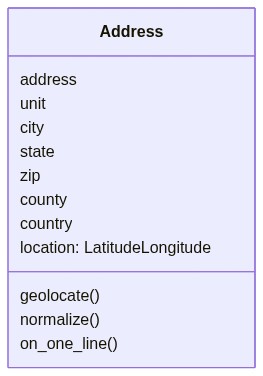

Address

The Address object is very powerful. It doesn't just store the different parts of an address: it can store a latitude and longitude, and it can be geolocated using Google as the engine to fill in information the user doesn't know (such as county).

Here's a class diagram for the key fields in the Address class:

If you want to verify the user's address was entered correctly, you have at least two options:

- Use the

address autocompletefeature. This tells Docassemble to use Google to fill-in the address as you type. - Use the

.normalize()method to correct any mistakes in the address after you collect it from the user. This will overwrite the user's inputs; see the full documentation to learn about alternatives.

Here's a sample interview that uses address autocomplete to fill-in the user's address as they type:

objects:

- the_address: Address

---

mandatory: True

code: |

results_screen

---

question: |

Enter an address

fields:

- Address: the_address.address

address autocomplete: True # This turns on auto completion

- Unit: the_address.unit

required: False

- City: the_address.city

- State: the_address.state

- Zip: the_address.zip

required: False

---

event: results_screen

question: |

Results

subquestion: |

${the_address}

${map_of(the_address)}

In the example above, we use the built-in map_of function to display a Google Map of the address.

Suppose you collected the user's address in the interview above. You could normalize it (fix it to match what Google thinks is a valid address) in an interview snippet like this:

mandatory: True

code: |

the_address.normalize()

One reason to use this would be to add the user's county and country without making them type those fields in. This could be helpful if you wanted to show the user a court that serves their county, while you know that most users don't know the name of their county.